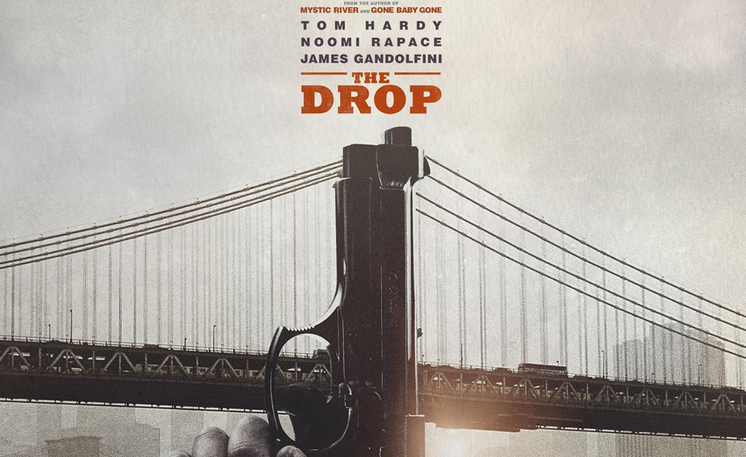

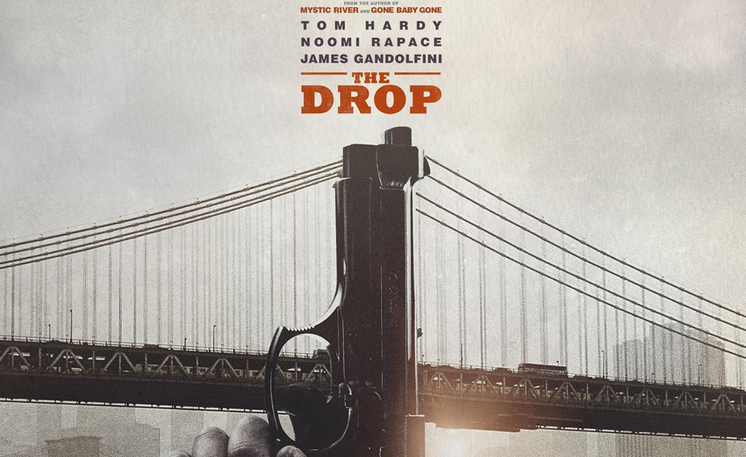

A drop is a term used to connote a location designated by - usually - the mob as a place where illicit money is temporarily held until it can be picked up by the powers that be. Betting money, drug money, money of all kinds, it appears. In this case, the drop happens to be the bar run by Gandolfini and Hardy, cousins with a somewhat murky past and a even murkier future. The Drop is based on a short story by Boston-based Dennis LeHane who also penned the screenplay, now set in Brooklyn, (as the film's poster alludes to) because the film's producers felt there were too many Boston-based crime movies (and I suppose that's a good thing).

The film is a fairly straight ahead crime-based character study - mostly of Hardy and Gandolfini. It's not quite The Friends of Eddie Coyle or Mean Streets or On The Waterfront, but it shares ingredients from each of these films.

The film is a fairly straight ahead crime-based character study - mostly of Hardy and Gandolfini. It's not quite The Friends of Eddie Coyle or Mean Streets or On The Waterfront, but it shares ingredients from each of these films.

There's no doubt Hardy, Gandolfini, and Rapace can act. Hardy, in particular, disappears into this role, his delivery reminiscent at times of Brando's beautiful loser in Waterfront. If Brando liked pigeons, Hardy likes pit bull puppies here, a classic script maxim being that, if you want to make your hero sympathetic, have him save the cat (title of scriptwriting manual) or, in this case, a puppy. And Gandolfini's last major screen role is a hell of a curtain call.

The film takes its time getting up to speed. There's a welcome introductory explanation of what a drop is (see above) and then we move chronologically through the tale of betrayal, possible love, vigilante justice, and perhaps - eventually - redemption.

Like most character studies with sub-narratives lurking in the background, eventually story must take over and The Drop's final 20 minutes are all story. No spoilers here, you'll have to see the film, but suffice it to say that The Drop works on you slowly, at times a little ham handedly, even awkwardly, but it manages to uh...redeem itself in it's final moments.

The film is a fairly straight ahead crime-based character study - mostly of Hardy and Gandolfini. It's not quite The Friends of Eddie Coyle or Mean Streets or On The Waterfront, but it shares ingredients from each of these films.

The film is a fairly straight ahead crime-based character study - mostly of Hardy and Gandolfini. It's not quite The Friends of Eddie Coyle or Mean Streets or On The Waterfront, but it shares ingredients from each of these films. There's no doubt Hardy, Gandolfini, and Rapace can act. Hardy, in particular, disappears into this role, his delivery reminiscent at times of Brando's beautiful loser in Waterfront. If Brando liked pigeons, Hardy likes pit bull puppies here, a classic script maxim being that, if you want to make your hero sympathetic, have him save the cat (title of scriptwriting manual) or, in this case, a puppy. And Gandolfini's last major screen role is a hell of a curtain call.

The film takes its time getting up to speed. There's a welcome introductory explanation of what a drop is (see above) and then we move chronologically through the tale of betrayal, possible love, vigilante justice, and perhaps - eventually - redemption.

Like most character studies with sub-narratives lurking in the background, eventually story must take over and The Drop's final 20 minutes are all story. No spoilers here, you'll have to see the film, but suffice it to say that The Drop works on you slowly, at times a little ham handedly, even awkwardly, but it manages to uh...redeem itself in it's final moments.

Comments

Post a Comment